Life In the Fast Lane

Picture yourself driving alone along your favorite stretch of highway, with no real urgency to get to your destination and with no other vehicles in sight. The one sure thing is that you will be traveling at your own speed - whatever pace feels right to you. But then imagine the moment when you first sense the tug of cars approaching and then nosing ahead of you, and then the rush of cars flying by at faster speeds. It is almost by instinct that you press down on the accelerator.

This analogy feels appropriate for most aspects of life today, when more information comes at us – and is consumed by us – constantly and at an ever-greater speed. Do you ever get the sense that with the world moving so quickly and changing so fast, it has become impossible to take any part of life at your own speed?

Source: Visual Capitalist, citing Cumulus Media.

With the tenth anniversary of Apple’s iPhone recently past, it seems fitting to reflect on the impact to us of a continuously connected world. The positive benefits are many; we can remain constantly in touch with our friends, family and children. We can be much more flexible in the logistics and hours of our working lives. We are able to connect more closely and immediately with our interests and passions and we certainly are more aware of the world around us in real time. We consume news as it occurs and not simply when it hits the airwaves or front page.

However, as is often the case with disruptive changes, there is a dark side that is more difficult to see.

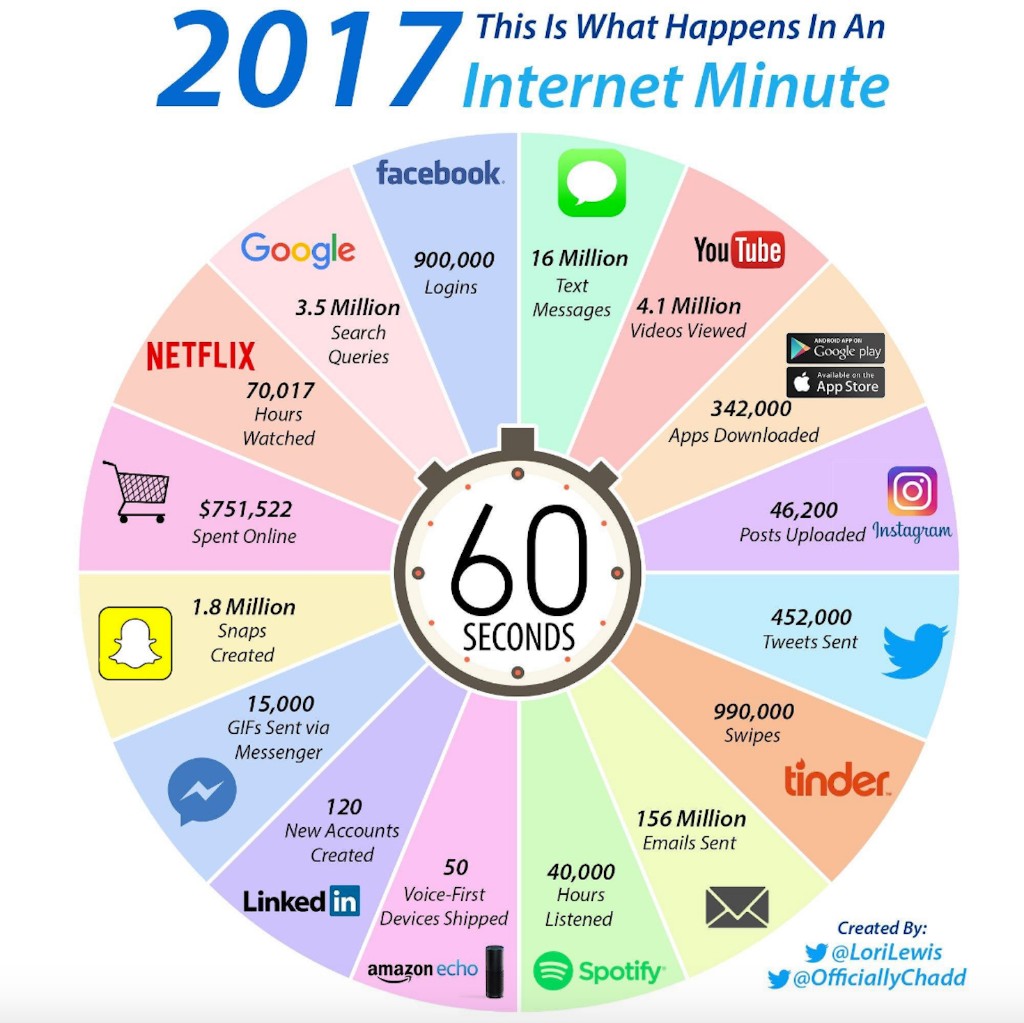

Continuous connection can front-load our lives and increase our sensitivity to outside opinion at the expense of facts. Facebook – a site whose 2.1 billion-person base of active monthly users represents over a quarter of the global population - estimates that its “Like” button is pressed 4.2 million times per minute. Views expressed in a continuously connected world are reinforced by simple consumption as much as by active “likes,” however. Per the figures in the chart shown at left, “An Internet Minute” sees 16 million text messages sent, 4.1 million YouTube videos viewed, 3.5 million Google searches performed, and so on.

With that level of consumption in mind, is it fair to say this world spins a little faster because opinions are immediate and often viral? Does that pace allow for fact-checking, and do we even require validation of "facts" that are presented to us? A growing body of social media psychology indicates that our attention is drawn toward - and our opinions and beliefs are shaped by - the number of likes and comments a story or picture has received.

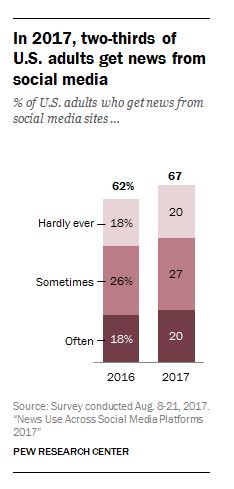

In an era that some media and political critics refer to as a “Post-Truth” due to the enormous influence of opinion and emotion on public conversation, the credibility of our news sources is hardly a trivial issue. And yet it seems that today our consumption of news is inextricably tied to the very same medium we rely on to express and affirm our opinions and preferences. In September of this year the Pew Research Center, a nonpartisan “fact-tank,” published survey results indicating that 67% of U.S. adults get news from social media sites. A November follow-up study revealed 45% of U.S. adults report using Facebook as a news source, and half of them use that site only.

If we find these survey results credible or even recognize them in our own experience, should we be surprised by an environment today in which it often feels that we rely more on "preferred facts" than... plain old facts?

If we find these survey results credible or even recognize them in our own experience, should we be surprised by an environment today in which it often feels that we rely more on "preferred facts" than... plain old facts?

Urging us deeper still into our "preferred facts" is a distaste for contradictory opinion or even evidence, suggests at least one study. Published in 2010 in Political Behavior, “When Corrections Fail: The Persistence of Political Misperceptions” looked at the impact of corrections on opinions research participants had formed based on misleading claims. Authors Brendan Nyhan and Jason Reifler, now professors at Dartmouth College and University of Exeter, respectively, thus coined the “the Backfire Effect.”

As stated in the study’s abstract:

We conducted four experiments in which subjects read mock news articles that included either a misleading claim from a politician, or a misleading claim and a correction. Results indicate that corrections frequently fail to reduce misperceptions among the targeted ideological group. We also document several instances of a “backfire effect” in which corrections actually increase misperceptions among the group in question.

The impact of continuous connection can also be seen and felt in the dulling of our “stopping cues.” Stopping cues are activities or sensations that signal the end of an activity or phase in our day; they are the pause buttons in our lives. They’re the deep breaths we hardly feel ourselves taking. Stopping cues lower our stress, clear our heads and help us to be more thoughtful and deliberate in our decisions.

For example, the end of the school day used to cue the end of a child’s daily period of immersion in a certain social environment – but now children have Facebook, carrying their social network with them into a time of day traditionally reserved for other activities or time with family. For adults, it used to be that when the work day ended, work was done – but now we have e-mail. It used to be that the last page of the newspaper or an anchor’s TV sign-off cued the end of the news day, but now we have streaming news and phone alerts. And of course, it used to be that the shopping day was done when the store closed - now we have Amazon. In the absence of stopping cues, we are keyed permanently into the stresses – negative and positive – and factors that make up our day. Without some kind of cue to rest, we have no opportunity to step outside of those factors in order to evaluate them more clearly and make decisions more deliberately.

The same powerful influences - those that have diminished stopping cues and accelerated consumption, reason and decision-making in all aspects our lives - can compress time horizons for all our decisions in a subtle and even subliminal manner. Financial practices and investment decisions are not immune to the pace at which the world moves, and neither are markets.

One of the most important factors in investing is the time horizon of the expected return; “long-term” and “stable” have long been the bywords of prudent investing. Stock markets have demonstrated convincingly over history that the longer your time horizon, the greater the opportunity to earn a positive result. We believe that short-term decision-making often leads to disappointing long-term outcomes, and in a continuously changing world, the temptation to act on the short-term will only result in a decision based on a reality that will have changed in “an internet minute.”

Is it possible to be a patient investor in a world set to hyper-speed? We believe so, and while the challenge is considerable, we believe it is outweighed by the necessity. In life and investing, we view today as a critical moment to resist the tug of cars flying by; to identify and cling to “stopping cues” that support well-reasoned decision-making.

Besides attributed information, this material is proprietary and may not be reproduced, transferred or distributed in any form without prior written permission from WST. WST reserves the right at any time and without notice to change, amend, or cease publication of the information. This material has been prepared solely for informative purposes. The information contained herein may include information that has been obtained from third party sources and has not been independently verified. It is made available on an “as is” basis without warranty. This document is intended for clients for informational purposes only and should not be otherwise disseminated to other third parties. Past performance or results should not be taken as an indication or guarantee of future performance or results, and no representation or warranty, express or implied is made regarding future performance or results. This document does not constitute an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to purchase, any security, future or other financial instrument or product.